2015 Report on the Use of Mobile Devices for Academic Purposes at the University of Washington

Tara Coffin, Henry Lyle & Abigail Evans

University of Washington Information Technology, Academic and Collaborative Applications

Executive Summary

Findings from the annual EDUCAUSE ECAR survey show a continued rise in the use of mobile devices for educational purposes among University of Washington (UW) students. Almost half of the instructors surveyed see the learning benefits of mobile devices but even more (63.0%) have concerns about their tendency to distract students. Instructors desire training on how to effectively use mobile devices as learning tools. However, instructors do not feel that UW makes mobile learning a priority. The following recommendations are intended to address the concerns and opportunities revealed by these findings:

Create evidence-based, best-practice recommendations and professional development opportunities

Further research on mobile device use at the UW is needed to generate best-practice recommendations for employing handheld mobile devices as a learning tool. Goals for the research, which would inform training and professional development opportunities offered to UW instructors, should include:

- Discovering student and faculty needs, challenges, and reservations regarding mobile learning, focusing on distraction, device ownership, and communication of expectations of in-class use;

- Surveying innovative mobile initiatives at other higher education institutions;

- Documenting mobile learning practices that show evidence for enhancing student learning and engagement, and do so in a range of teaching and learning contexts;

- Determining the best strategy for delivering professional development opportunities (e.g., workshops vs. online training videos)

Develop a mobile teaching and learning initiative

While UW instructors feel that handheld mobile devices can be used to enhance student learning, they indicate a lack of institutional support for using these devices effectively. The UW can begin to resolve this issue by developing a mobile teaching and learning initiative based on the findings of the research and its deliverables.

Introduction

The UW is one of over 250 institutions of higher education participating in the EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research (ECAR) survey of technology in higher education. This annual survey gives UW-IT a valuable opportunity to learn how UW students and instructors use and perceive educational technologies, and to better assess the changing technology landscape at the UW. The 2015 ECAR survey draws attention to growth and transitions in the arena of mobile devices as tools for learning and teaching. Illustrating trends in device use and perceptions of utility, the survey results offer insight into the specific roles handheld mobile devices fill for students and faculty. By tracking these trends, UW-IT is better able to identify the emerging needs of faculty and students, delivering the tools and support necessary for the UW community to harness mobile devices as educational tools.

Findings

In this section, we summarize patterns in handheld mobile device ownership and discuss how these devices are used for educational purposes by instructors and students at the UW. A total of 638 UW students and 426 UW instructors took the 2015 ECAR survey. Pearson’s chi-square test was used to explore potential statistical differences between comparison groups.

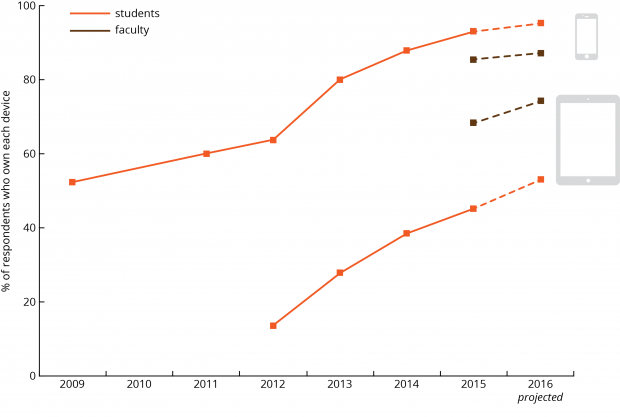

Mobile device ownership continues to increase at the UW

Mobile device ownership increased more than was projected by ECAR in 2015, continuing trends observed over the past six years (see Figure 1). While only 38.5% of students reported owning a tablet in 2014, by 2015 this percentage had increased to 45.2%. Smartphone ownership among students also increased from 87.9% in 2014 to 93.0% in 2015. Device ownership differs significantly between UW students and faculty. For example, the 2015 ECAR survey revealed that tablet ownership is higher among instructors than students (68.3% of faculty, compared to 45.2% of students, p<0.005), while more students than instructors own a smartphone (93.0% of students compared to 85.5% of faculty, p<0.005). Device ownership for UW faculty is projected to increase between 2015 and 2016.

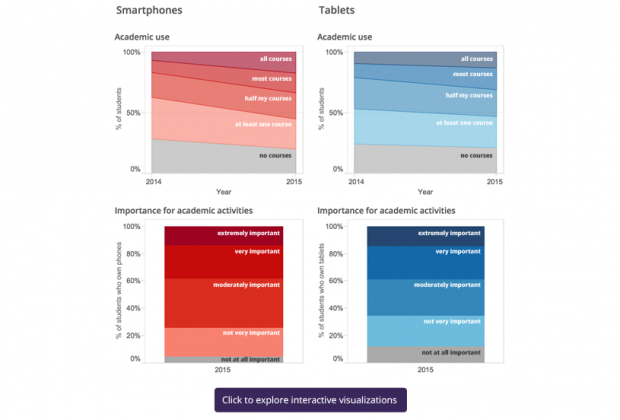

Students continue to use their handheld mobile devices for educational purposes

The in-class use of handheld mobile devices for educational purposes decreased slightly in 2015, yet the overall use of these devices for educational purposes increased, continuing the trend seen from 2013 to 2014. In 2014, 75.9% of UW students who owned a tablet reported using tablets in class for academic purposes, decreasing to 68.0% in 2015. However, when asked about academic use of tablets more broadly than just in class, 79.2% of tablet owners reported using them for at least one class. The same trend was seen in the use of smartphones for academic purposes, with the percentage of students who indicated using their smartphone for academic purposes in class decreasing slightly from 71.7% in 2014 to 70.3% in 2015. When asked about academic use of smartphones more broadly, 79.9% of smartphone owners reported using them for at least one class.

Students were also asked to reflect on the importance of their handheld devices for academic and administrative activities. In the 2015 survey, 74.6% of students said smartphones were important for administrative activities1, compared to 61.3% who indicated that was the case for tablets. Likewise, 74.4% of students reported that smartphones were important for academic activities2, while 65.0% of students indicated tablets were important for these tasks. The majority of students who used handheld devices for academic purposes in 2014 felt that they were important to their academic success—64.6% for tablets and 71.9% for smartphones. This did not change considerably in 2015, with 71.5% of tablet users and 65.0% of smartphone users indicating that the devices were important to their academic success.

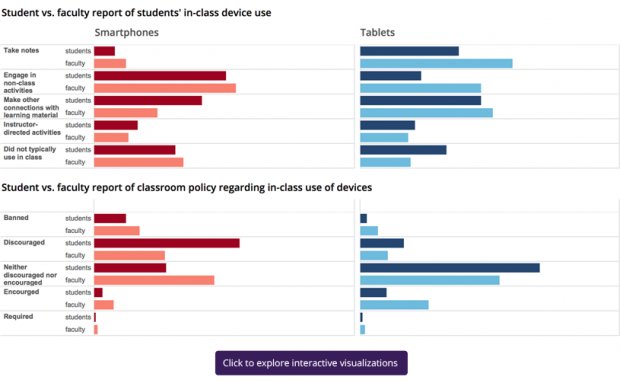

Handheld devices are used for a range of activities in class

Students report using smartphones and tablets to engage in a number of educational tasks during class. For example, 41.4% of UW students who own smartphones report using them to make other connections to the learning material, and 46.7% of students use their tablets in this fashion (See Table 1). When taking a closer look at in-class usage among students who indicate they own both devices, data reveals that students use their smartphones and tablets in similar ways with two major exceptions: taking notes and engaging in non-class activities. For example, 37.6% of students who own both devices reported using their tablets to take notes compared to just 8.8% who take notes with their smartphones, suggesting a preference for tablets for this activity. The reverse is true for non-class activities, with 50.6% indicating that they use their smartphones in this way compared to 22.9% for tablets.

Data indicates that students want to be better equipped at using their devices for in-class activities. For example, in 2014, 23.0% of UW students indicated they would be more effective if better skilled at using smartphones during class. This percentage increased to 31.7% in 2015 (p<0.005).

| in-class use of Smartphones | in-class use of Tablets | |||

| UW Students (n=561) | UW Faculty (n=90) | UW Students (n=255) | UW Faculty (n=92) | |

| Take notes | 8.0% | 12.2% | 38.0% | 58.7% |

| Engage in non-class activities | 50.8% | 54.4% | 23.5% | 46.7% |

| Make other connections with the learning material | 41.4% | 24.4% | 46.7% | 51.1% |

| Used for instructor-directed activities | 16.8% | 13.3% | 21.2% | 18.5% |

| Did not typically use in class | 31.2% | 34.4% | 33.3% | 19.6% |

Table 1: Student device use in class and faculty perception of student in-class device use. Only students who indicated that they owned each device were included.

Write-in responses from both students and faculty describe a unique role filled by tablets in the classroom—generating annotated lecture notes. When asked what instructors can do with technology to enhance their academic success, one student noted that it is helpful when instructors “write notes on their digital lecture slides with tablets and upload them online,” noting that this practice is “really helpful for reviewing material.” Another student added that this practice was instrumental for “clarifying notes.” Likewise, when asked to recall their best experience with teaching technology over the past year, one faculty member described using their tablet to present lecture slides in a large class and “being able to write with a stylus on my powerpoint presentation,” and several others chimed in to report favorable experiences with this feature.

Students and faculty are not always on the same page regarding in-class device use

Faculty perceptions of how students use their devices are inconsistent with student reports of use for some in-class activities. UW faculty perceive off-task usage of tablets as far greater than students report (p<0.01). Additionally, while 41.4% of students indicated they use their smartphones in class to make other connections with the learning material, only 24.4% of faculty indicate that students use their smartphones for these purposes (p<0.01). Interestingly, faculty feel their students use their tablets more frequently for taking notes than students report (p<0.05). See Table 1 for additional details concerning these inconsistencies.

Further inconsistencies between students and faculty are seen in their perceptions of policy. Students indicate experiencing a more restrictive in-class policy for mobile device use than faculty report. 26.4% of faculty report encouraging in-class tablet use compared to only 10.3% of students who say that tablets are encouraged (p<0.001). Consistent with trends observed in 2014, 68.2% of students say that smartphones are typically discouraged or banned in their class compared to 44.9% of instructors who report enforcing these policies (p<0.001).

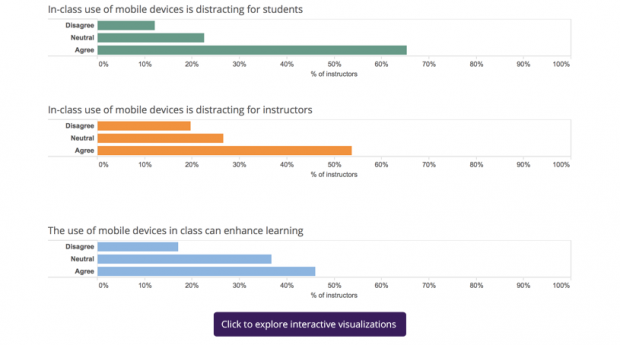

Many instructors believe mobile devices have the capacity to enhance learning, but are a distraction in class

UW instructors tend toward a positive view of mobile devices as tools that can enhance learning. 42.9% agree that mobile devices have the capacity to enhance learning while only 17.2% disagree. This remains largely unchanged since the 2014 ECAR survey.

More instructors felt that their assignments took advantage of students’ access to mobile devices in 2015 than in 2014—24.0% of faculty in 2015 compared to 18.9% in 2014 (p<0.005). But, compared to their peers at other doctoral institutions, UW instructors disagree or are unsure whether their institution makes mobile learning a priority. In 2015, over a quarter of UW faculty respondents were unsure, and about one third of respondents said they disagreed that the UW makes mobile learning a priority. Of the remaining faculty participants, only 6.5% of faculty respondents agreed that the UW prioritizes mobile learning, compared to 7.7% of their peers at other institutions (p=0.012).

Despite recognizing, or at least not dismissing, the potential of mobile devices to enhance learning, UW instructors continue to see in-class use of mobile devices as distracting. In 2014, 70.0% of UW instructors indicated that in-class use of mobile devices is distracting. These concerns persisted in 2015, with 63.0% of instructors indicating that handheld mobile devices are a distraction for students and 54.9% of students reporting that in-class use of devices is distracting for other students.

Discussion

Mobile learning in higher education is quickly evolving

As mobile device ownership increases among students and instructors, it stands to reason that the use of mobile devices for academic purposes will rise, especially considering college students are among the most rapid adopters of cell phone technology (Lepp, Barkley & Karpinski, 2015). UW students feel mobile devices are important to their academic success, and many UW instructors feel that these devices can enhance learning. These findings are consistent with other research that suggests mobile devices have the capacity to improve student engagement, both in and out of the classroom, and enhance learning (Parcha, 2014; Blessing, Blessing & Fleck, 2012; McArthur & Bostedo-Conway, 2012; Tyma, 2011). While it seems likely that mobile learning at the UW is poised to climb sharply, a few issues surfaced from analysis of the ECAR survey data: the distraction mobile devices cause, instructor misunderstanding of student use of mobile devices, student confusion about in-class policies, and lack of institutional support for instructors.

Distraction

The 2015 ECAR survey found that about half of UW students use their smartphones to engage in non-class related activities and that both instructors and students consider mobile devices in the classroom to be distracting. A 2013 study painted a picture of what this off-task use looks like, revealing that 86.0% of university students use their devices to text, and two thirds of students report connecting to social media (McCoy, 2013). There is also strong evidence that such behavior has a negative impact on student learning. For example, one study found that students who engaged in non-class related activities on their mobile devices during class performed worse academically than their peers who refrained from such off-task behavior (Kuznekoff, Munz & Titsworth, 2015). The knee-jerk reaction to these findings is to do what many instructors have done—ban mobile devices from the classroom. Given the positive impact mobile devices can have on the learning experience, an alternative approach is to evaluate solutions for mitigating distraction.

Communication

Results indicate a communication disconnect between instructors and students regarding in-class policies for the use of mobile technologies. Students report much stricter policies than instructors indicated implementing, suggesting that instructors are not clear about their policies and students are playing it safe by assuming that use is prohibited. Likewise, students report using their devices in class in ways not anticipated by their instructors, such as using smartphones to make connections with the learning material. Instructors also incorrectly overestimated the off-task behavior of tablet users. These discrepancies between UW student self-reports and faculty perceptions of in-class handheld device use suggest that instructors may be underestimating the value of these devices to students in their academic lives, and/or do not have a clear understanding of how students are using their mobile devices.

Support

Even in light of the research supporting the utility of mobile devices, paired with reported instructor interest, UW instructors seem hesitant to explore the relatively new pedagogical terrain of handheld mobile devices. While 42.9% of instructors felt that the use of mobile devices in the classroom can enhance learning, only 24.0% created assignments that take advantage of student access to mobile technologies. ECAR data suggests that this reluctance may have something to do with a lack of institutional support – almost half of those surveyed desired more training around effectively incorporating mobile devices into their courses. Without institutional support of the academic use of handheld mobile devices, mobile teaching and learning at the UW will not see its full potential.

Tablets vs. smartphones

While students report using tablets in class in similar ways to smartphones, there are two key differences: many more students use their tablets for note-taking than their smartphone and half as many students use their tablet to engage in non-class activities than their smartphone. The finding about note-taking is not surprising given the limited text entry functionality on a small touch screen. The root of students’ apparent preference of smartphones over tablets for off-task behavior in class, however, is unclear. This preference may be due to the varying affordances of different devices or it may point to a difference in student attitudes toward the role of each device in their academic and non-academic lives. Whichever the case, the fact that these devices impact student distraction unequally may require a mobile learning approach that is tailored to the device.

Recommendations

Ensuring successful mobile teaching and learning at the UW requires two efforts. First, we need to gain a better understanding of barriers to successful mobile learning (e.g., distraction), and develop evidence-based, best-practice recommendations for instructors. Second, the UW needs to clearly articulate a mobile teaching and learning strategy that guides, encourages, and supports the effective use of mobile technologies both inside and outside the classroom.

Create evidence-based, best-practice recommendations and professional development opportunities

Further research on mobile device use at the UW is needed to generate best-practice recommendations for employing handheld mobile devices as a learning tool. Goals for the research, which would inform training and professional development opportunities offered to UW instructors, should include:

- Discovering student and faculty needs, challenges, and reservations regarding mobile learning, focusing on distraction, device ownership, and communicating expectations of in-class use;

- Surveying innovative mobile initiatives at other higher education institutions;

- Documenting mobile learning practices that show evidence for enhancing student learning and engagement, and do so in a range of teaching and learning contexts;

- Determining the best strategy for delivering professional development opportunities (e.g., workshops vs. online training videos)

Develop a mobile teaching and learning initiative

While UW instructors feel that handheld mobile devices can be use to enhance student learning, they indicate there is a lack of institutional support for using these devices effectively. The UW can begin to resolve this issue by developing a mobile teaching and learning initiative based on the findings derived from the research study and its deliverables (listed in the previous paragraph).

References

Blessing, S. B., Blessing, J. S., & Fleck, B. K. B. (2012). Using Twitter to reinforce classroom concepts. Teaching of Psychology, 39, 268–271.

Kuznekoff, J.H., Munz, S., & Titsworth, S. (2015). Mobile Phones in the Classroom: Examining the Effects of Texting, Twitter, and Message Content on Student Learning, Communication Education, 64:3, 344-365.

Lepp, A., Barkley, J.E., & Karpinski, A.c. (2015). The relationship between cell phone use and academic performance in a sample of U.S. College Students. Sage Open, 1-9.

McArthur, J. A., & Bostedo-Conway, K. (2012). Exploring the relationship between studentinstructor interaction on Twitter and student perceptions of teacher behaviors. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 24, 286–292.

McCoy, B. R. (2013). Digital distractions in the classroom: Student classroom use of digital devices for non-class related purposes. Journal of Media Education, 4, 5–14.

Parcha, J. M. (2014). Accommodating Twitter: Communication accommodation theory and classroom interactions. Communication Teacher, 28, 229–235.

Tyma, A. (2011). Connecting with what is out there!: Using Twitter in the large lecture. Communication Teacher, 25, 175–181.

1 The 2015 ECAR survey defines administrative activities as accessing library resources and course content, checking grades, registering for courses, tracking financial aid, etc.

2 The 2015 ECAR survey defines academic activities as reading text messages (about class related issues), communicating with students and instructors about class related issues outside of class, taking notes in class, and looking up information related to the learning material.